Window 24. As I am following the Swedish system of advent calendars, today is the last window, not the 25th as in the UK. So here is the final word: Kalle Anka. This is the Swedish name for Donald Duck – a Disney character with a strong, and unexpected, connection to Swedish Christmas.

Traditional Christmas celebrations on Christmas Eve in Sweden get off to a slow start usually. It all begins with a Christmas breakfast, consisting of rice porridge, wort bread, ham and Christmas cheese, amongst other things. After breakfast, some people go for a walk, some go to church, others begin the preparation for the Christmas julbord (buffet).

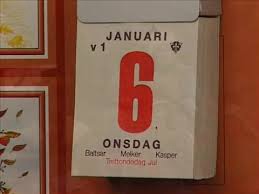

When to eat julbord differs from family to family. For some, it’s at lunch time, for others it more towards late afternoon. One surprising time marker is Kalle Anka (Donald Duck).

Every Christmas Eve since 1960, the Disney show ‘From All of Us to All of You’ featuring Donald Duck and his friends has been broadcasted on Swedish television at 3pm (now 3.05pm). Every single year. A very weird tradition for someone like me who grew up listening to the Queen’s speech on Christmas Day at 3pm. In the UK we have the monarch. In Sweden, Donald Duck.

So the discussion in Swedish homes is ‘should we eat before or after Kalle?’.

Today, Kalle Anka is watched as a sentimental tradition, or as background noise on Christmas Eve. But in the 1960’s when it began, it was the only time of the year that cartoons were shown on tv, so it was a Christmas treat. Since it’s been broadcast for almost 60 years, it is an integral part of what many Swedes associate with Christmas.

After Kalle Anka och julbord, it’s time for a visit from Tomten with gift-giving. This is followed usually by more food and drink. Some people conclude the day with a Midnight service at their local church.

Christmas is, like many places around the world, a time of overconsumption. Enormous amounts of food are left over and eaten during the following days.

In Sweden, Christmas Day and Boxing Day are both Public holidays – and the official end of Christmas is January 13th. Then it is time to traditionally throw out the Christmas tree. The lights in the windows have usually disappeared by February.

And as the daylight slowly returns to Sweden, people start planning for the lighter and warmer time of the year. And Christmas fades into memory…until next December.